Excerpt from the Frederick News-Post:

by Christina Martinkosky

As the weather chills and the holidays draw near, thoughts often turn to food. Thanksgiving is quickly approaching, and home cooks everywhere are debating the final details of their menu.

This national tradition began back in 1621 when pilgrims and members of the Wampanoag tribe sat down to dine on fowl, deer and locally grown crops. Thanksgiving didn’t become an official, annual holiday, however, until President Lincoln issued a Thanksgiving proclamation in 1863. Since then, family and friends have broken bread and given thanks for the harvest collected.

The modern Thanksgiving feast is made up of food produced from across the country and beyond. The turkey, the centerpiece of most meals, may easily have come from Minnesota or elsewhere in the Midwest. Your family could also be enjoying cranberries from Wisconsin, sweet potatoes from Arizona and green beans from Florida.

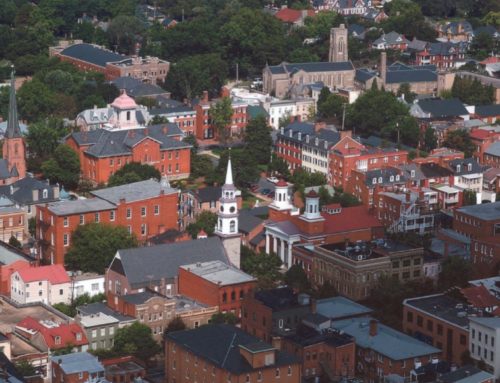

Of course, historically, the food gathered for the Thanksgiving meal was locally sourced. But how did this transformation happen? The full story is long and complex. But few realize the important role Frederick played in the food distribution revolution.

One of the key innovations in food preservation and transportation is canning. Humans have dried, salted and fermented foods since before recorded history. But preserving food by heat-treating and then sealing it in airtight containers was not developed until the late 18th century.

In 1810, an Englishman, Peter Durand, developed a method of sealing food into unbreakable tin containers. This technique soon spread across the Atlantic, and the first canning facility in the United States was established in New York by 1812.

As canning technology developed, a new industry slowly grew along the East Coast, especially in the Mid-Atlantic. The emerging industry began in the mid-Maryland region in the 1860s and accelerated in the 1890s. The local economy was consequently transformed from one of producing agricultural raw materials to one of transporting and processing them.

In Frederick, the canning industry was introduced by Louis McMurray in 1868 with the opening of his facility at Bentz and South streets. McMurray contracted with local farmers to grow several hundred acres of sweet corn and 100 acres of tomatoes and peas.

The concept of monoculture, the agricultural practice of producing a single crop, was foreign to local farmers, who viewed the practice as risky. The potential to transport local crops to distant locations was not understood.

One farmer was quoted as saying, “Mr. McMurray, don’t you think you are doing very wrong? No sane man would plant that much corn and tomatoes; they would not be used in Frederick in all your life.”

Perhaps, not surprisingly, the local farmers were unconvinced of McMurray’s business plan and did not completely invest in the venture, which led to a poor harvest with less corn to pack than expected. Not to be discouraged, McMurray rented, and eventually bought, farmland to grow his own produce. He also patented several mechanical improvements to the heating and canning process, which meant produce could be processed more efficiently.

Locally, the new industry provided seasonal employment to over 1,000 men, women and children. Globally, McMurray was producing and shipping high-quality canned fruits and vegetables to Europe and around Cape Horn to California. He received the highest awards and diplomas for canned sugar corn and canned oysters at the 1876 Centennial Exposition and the 1878 Paris Exposition. By the time of Louis McMurray’s death in 1888, his canning establishment was reputed to be the largest in the world.

Operations at McMurray’s Frederick factory ceased soon after his death, but the canning industry in Frederick had already taken root. Throughout the county at least 23 companies ran their own packing facilities. Although the “golden age” of local canning ended by the 1970s, Frederick’s early contribution to the industry can’t be disputed.

Physical remnants of this industrial past can still be seen. If you have guests visiting for the holiday, take them to the old Monocacy Canning Co. on South East Street, which has been adaptively reused as the Frederick Visitor Center. Just a block away, on Commerce Street, is the former Frederick City Packing Co., which has been recently protected by a Historic Preservation overlay. And if you are seeking an actual taste of Frederick canning history to go along with your Thanksgiving feast, look no further than McCutcheon’s Apple Products.