Excerpt from Frederick News-Post

By Lisa Mroszczyk Murphy

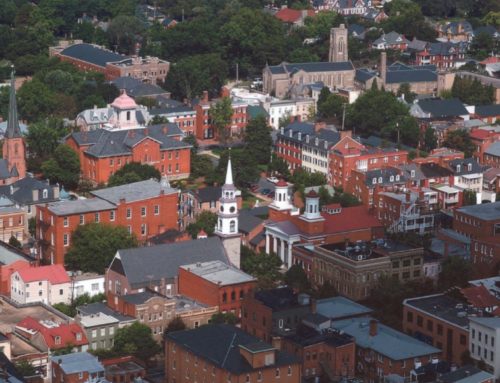

As Black History Month wraps up this week, we are taking a look at the history of two churches linked by their architecture and their long-standing importance to the black communities that they serve.

The Asbury United Methodist Church stands prominently at the corner of West All Saints and South Court streets and features red brick walls with cast stone accents, buttresses, pointed arch windows, and a castle-like tower.

Dating from 1921, the Gothic Revival church was designed by Frederick architect Benjamin Evard Kepner and constructed by local contractors Hahn and Betson. Kepner designed many important Frederick buildings such as the Pythian Castle on Court Street, the Rosenour Building at the northwest corner of Market and Church streets, and the Frederick Trust Co. building at the southeast corner of Market and Third streets.

While this church building became an important architectural and community fixture in the 20th century, it had its origins on East All Saints Street when the all-white All Saints Church, the street’s namesake, moved to West Church Street in 1864, leaving the old church to be acquired by the black community.

The church on East All Saints Street was renamed the “Old Hill Church” before it was renamed the Asbury Methodist Episcopal Church when it was incorporated by an act of the General Assembly of Maryland in 1870. In 1912, the church purchased the lot at West All Saints Street and Brewers Alley (now Court Street) for a new church building. When the new church was completed in 1921, its community influence flourished with a wide range of ministries and fellowship programs and a growing membership.

The Quinn Chapel on East Third Street is another church that served the black community primarily living in the area of East Fourth and Fifth streets and present-day Maxwell Alley and East Street. In 1923, the Gothic Revival façade and bell tower were added to the modest 1855 church. The pointed arch windows, buttresses, cast stone accents, and castellated tower are strikingly similar to the features of the Asbury Church.

From a newspaper account of the alterations to Quinn Chapel, we know that Hahn and Betson were also the contractors, and although the architect is not noted, it is quite possible that Kepner was involved.

Like the Asbury Church, the Quinn Chapel dates to the early 19th century, when a group of free black residents formed the Bethel Congregation and joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In the congregation’s earliest days, it used a log building adjacent to the church’s current site for worship.

In 1835, the church was renamed the Quinn Chapel AME Church after William Paul Quinn, the highly regarded fourth bishop of the AME Church, and in 1855, a new two-story church was constructed over the basement machine shop at the present church site. Of particular importance, the Quinn Chapel basement served as a hospital for soldiers wounded in the Battle of Monocacy and also housed a school for blacks after the Civil War.

The Gothic Revival was a popular style for churches generally starting in the mid-19th century, and several others of this type can be found in Frederick. The style is largely characterized by the pointed arch windows and entrances, castle-like towers, and steeply sloped roofs. Gothic Revival, which harks back to the medieval era, conveys a sense of permanence and transcendence, which is also an accurate reflection of these long-standing institutions in Frederick’s black community.

Joy Onley’s book “Memories of Frederick Over on the Other Side” provided significant background information for this article, along with anniversary publications by both the Asbury United Methodist Church and the Quinn AME Church. Please send your comments and questions to preservationmatters@cityoffrederick.com.